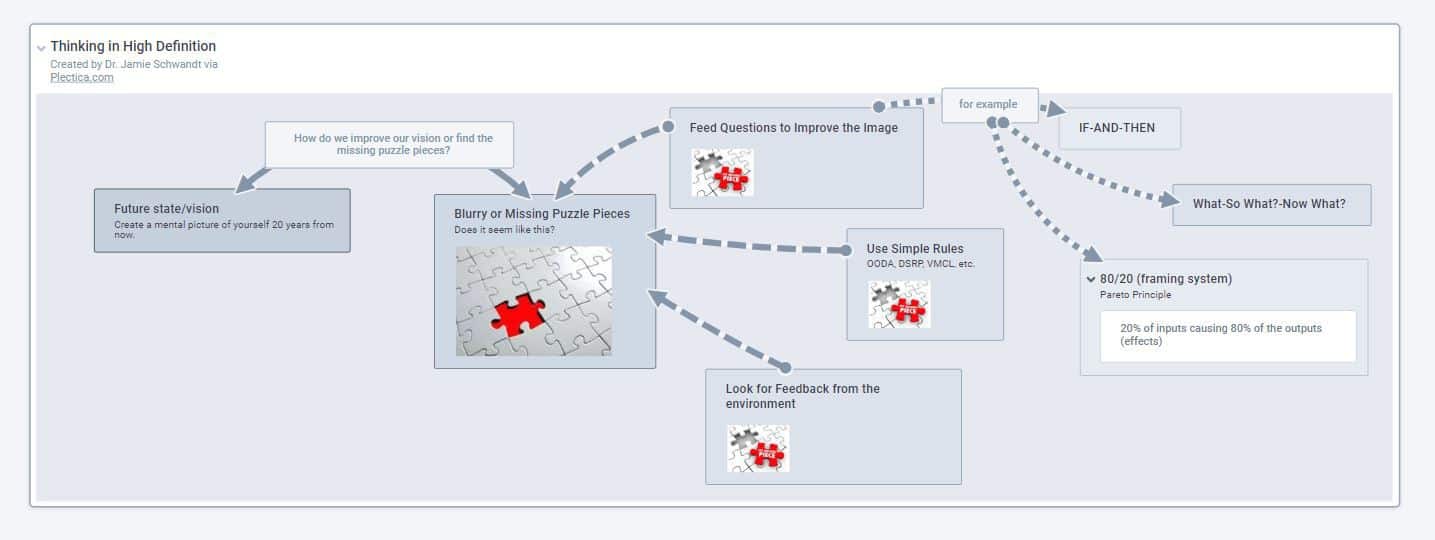

What do you see? Is it a blurry or fuzzy image? Is it like a puzzle with missing pieces? How do we improve our vision or find the missing puzzle pieces? I found 9 game changing tips on how to write goals and actually reach them.and split them into 3 categories to explain them: Questions to improve the image, simple rules, and feedback.

How to write goals and actually reach them

Let’s examine these 9 game changing tips on how to identify these missing pieces and how you can find them.

Questions to improve the image — Your goal

1. If — and — then (Killer tip!)

IF we seek to identify goals to improve our life in twenty years from now — AND we see a blurry image in our mind — THEN we should use these powerful tips to write and action our goals. This is no different than computer coding. In How To Hack Your Brain and Reprogram Your Habits (Like a Computer), I discuss how to use this technique to overcome bad habits. Yet, this technique can also be used to write and action goals. Let’s examine how this works: IF x happens — THEN I will do y. IF = cause AND = necessary condition or correlation THEN = effect Example: IF: If I notice I have gained weight. AND: And I want to start exercising. THEN: I will create triggers to ensure I exercise every morning. To illustrate this point further, let’s examine an exercise trigger: IF: If I sleep in my (clean) running clothing. AND: And I use technology, such as the Pavlok Shock Clock to wake myself up in the morning. THEN: Then I will wake-up at 4am and run every morning.

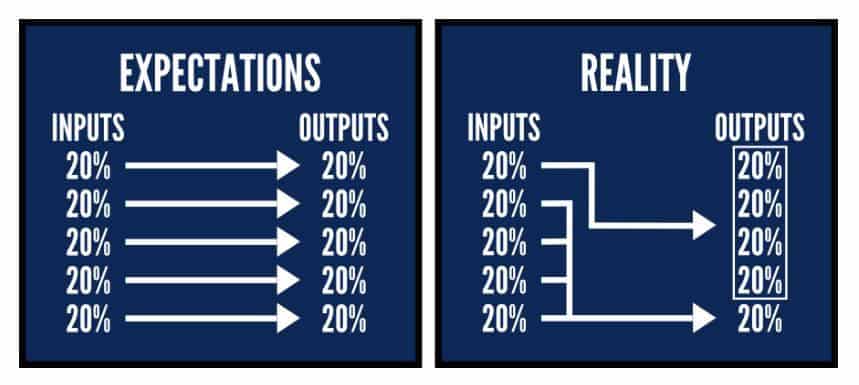

2. 80/20 Rule

The 80/20 Rule (otherwise known as the Pareto principle) is the law of the vital few. It states that 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes.

Inputs or Causes = 20% Outputs or Effects = 80% 20% of our inputs cause 80% of our outputs. The key is to identify the 20% of your actions that are creating 80% of your rewards. If you are able to successfully identify the 20%, then only do those actions. Example: If what you do 80% of the time only brings you 20% of your results, then stop doing those actions. If what you do 20% of the time brings you 80% of your results, then only perform those actions. Another example can be found in the workplace: If you perform the following tasks: 1) make phone calls, 2) check e-mail, 3) write long reports, 4) participate in long meetings, 5) visit work-site locations to improve a process, 6) visit work-site locations to identify problems, 7) speak with employees directly to identify problems, 8) spend long hours creating PowerPoint presentations, 9) micromanage employees tasks, 10) micromanage employees attendance, etc. And you determine that only 20% of these tasks produce 80% of the direct positive results to you and your organization. Then only perform those 20%. This means you might only perform the following: 5) visit work-site locations to improve a process and 6) visit work-site locations to identify problems. In Joel Runyon’s article about the 80/20 rule, he provides advice for a diet. He says,[1]

3. What? — So What? — Now What? (Killer tip!)

Developed in 1970 by Terry Borton, Borton’s Development Framework provides us a straightforward approach to anything by asking three simple questions: What?, So What?, Now What? In Razor-Sharp Thinking: The What-Why Method, I wrote about the power of this simple approach. What? The experience… What happened? So What? Why was it important… What is the bottom line up front (BLUF)? Now What? What are you going to do now? Example: What? What happened to trigger a new goal? Let’s say you find it hard to breath while walking. So What? This is the reason (or the why) to improve your health. If you find that you lose your breath while walking, and you are a smoker, then you have potentially identified the problem. Now What? This is your plan of action. For example: If you lose your breath while walking, and you are a smoker, then you need to quit smoking.

Simple rules

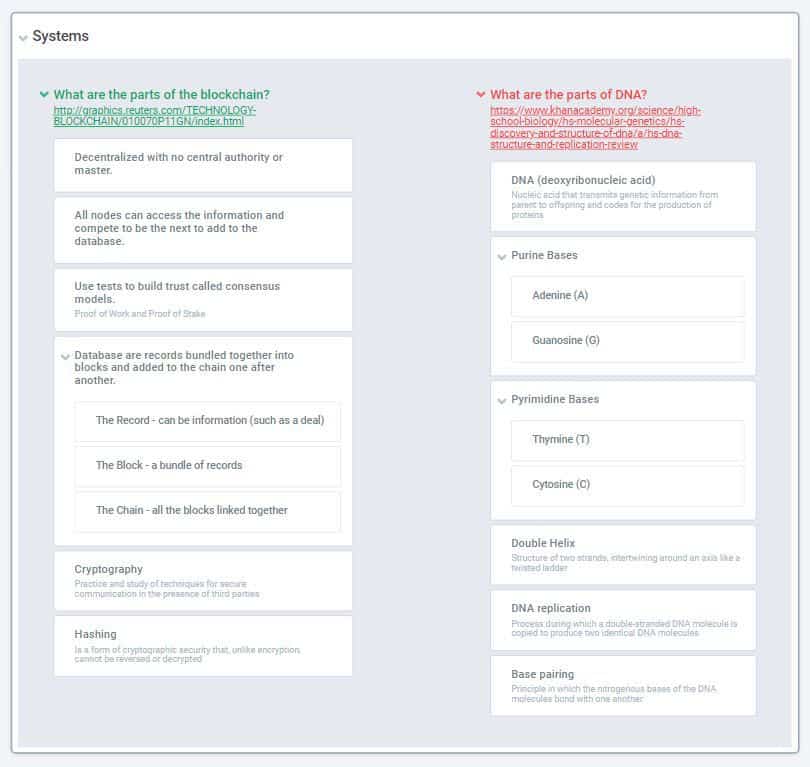

4. DSRP (Killer tip!)

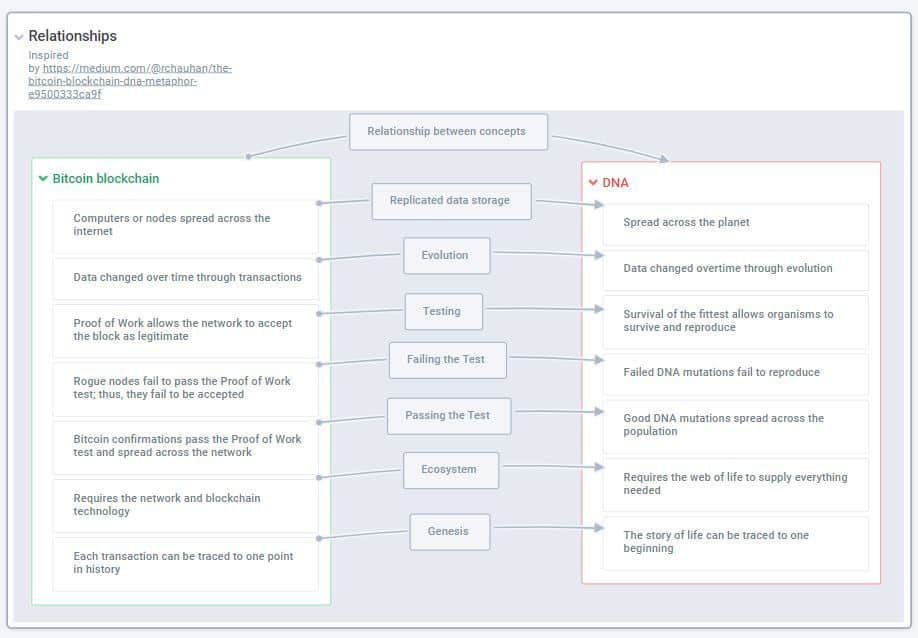

Systems Thinking v2.0 (DSRP) was developed by systems theorists Derek and Laura Cabrera. In Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems, the Cabrera’s surmise, DSRP is predicated on the idea that systems thinking is a complex adaptive system (CAS) with four underlying rules: Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, and Perspectives. DSRP is a way to use simple rules to understand difficult and confusing concepts. Let’s look at the simple rules with examples of how to use them in understanding the confusing concept of blockchain technology. Distinctions (Identity and Other) We must first identify what something is and what it is not.

Systems (Part and Whole) Once we have made clear distinctions we then examine the part-whole structure for blockchain and something else we are already knowledgeable with.

Relationships (Cause and effect) After we analyze the part-whole structure for both concepts, we then look for relationships between ideas.

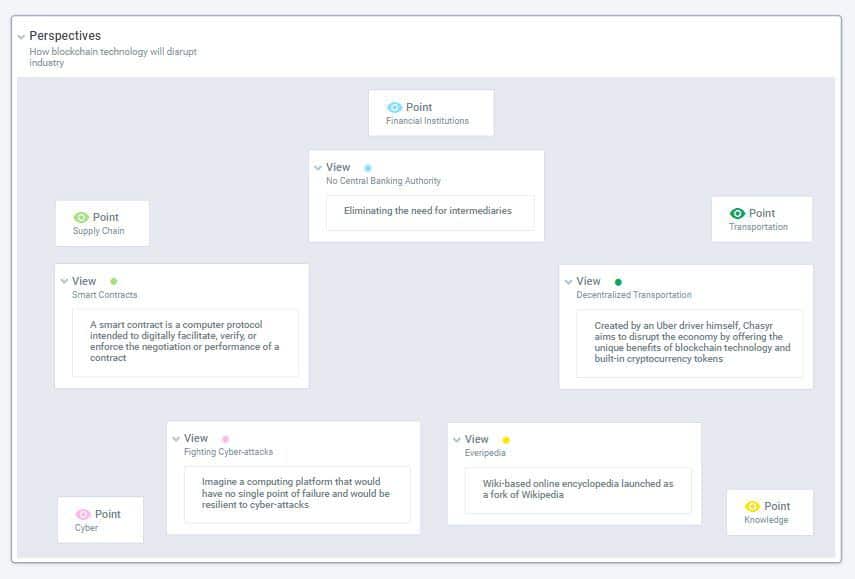

Perspectives (Point and view) Finally, we can then examine the different perspectives of blockchain technology from a point (i.e. supply chain) and a view (i.e. smart contracts).

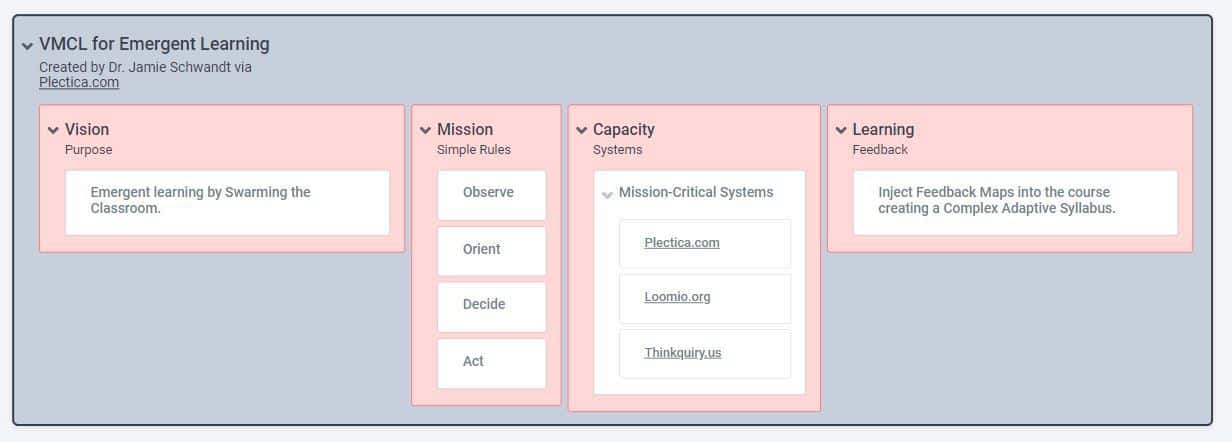

5. VMCL (Killer tip!)

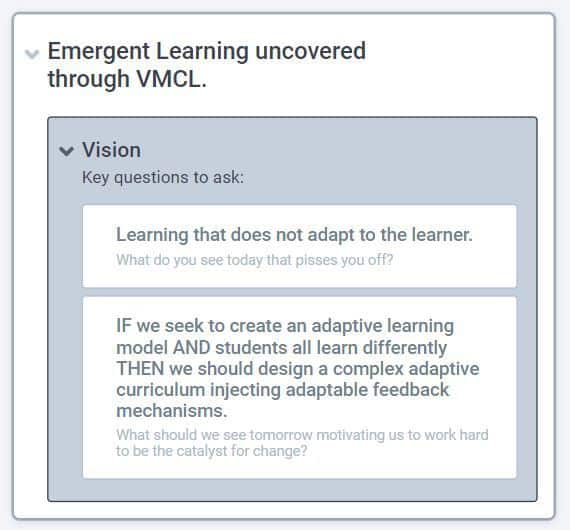

Derek and Laura Cabrera have also developed simple rules for any organization in their most recent book Flock Not Clock: Align people, processes, and systems to achieve your vision. In fact, I used these simple rules to develop my vision (Emergent Learning by Swarming the Classroom) for courses I teach at Fort Hays State University (FHSU) in Hays, Kansas. Let’s take a look at these rules and examples of how you can use them. Vision (your desired future state or goal)

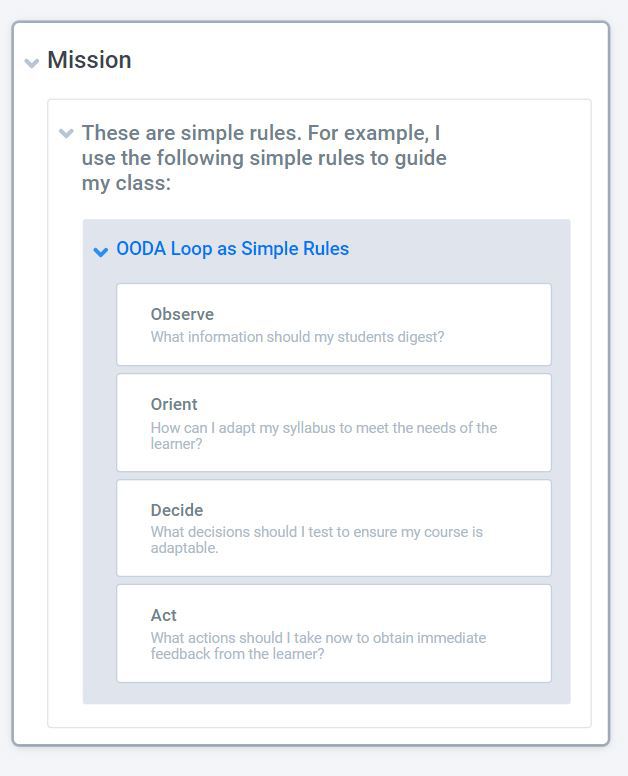

Mission (our repeatable actions that bring about the vision… simple rules)

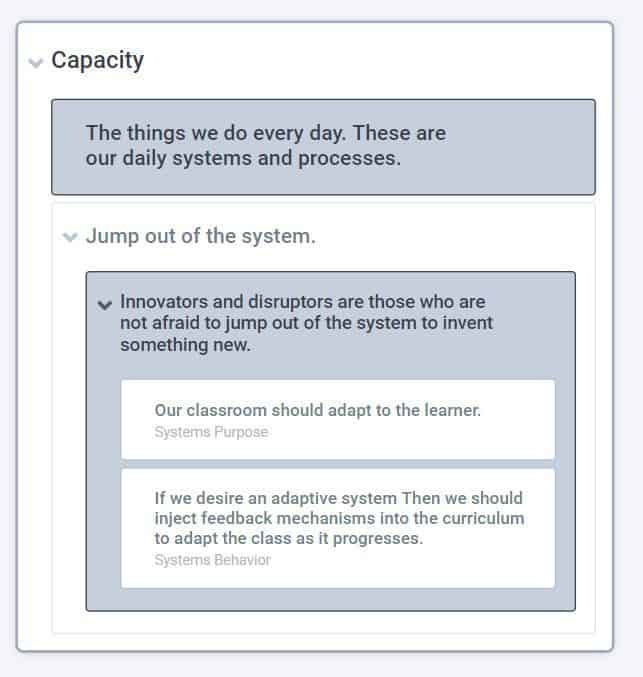

Capacity (our systems or processes that provide readiness to execute the mission)

Learning (our continuous improvements of systems of capacity based on feedback from the external environment)

Finally, here is a summary of VMCL for Emergent Learning.

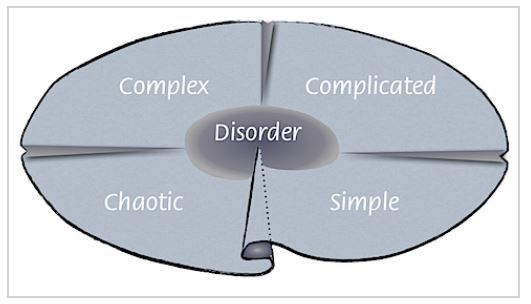

6. Cynefin Framework

Developed by Dave Snowden, the Cynefin Framework is a conceptual way to assist decision makers in making decisions. For a detailed examination of the framework, I recommend reading my article How to Thrive in Chaos. This framework provides simple rules (or domains) for identifying where a problem resides and the tools to use to solve a problem. The Cynefin Framework is essentially 5 domains. Let’s briefly examine four of the five domains (leaving out disorder) with a description, a metaphor, and an example: Simple (systems are stable and we can see clear cause-and-effect relationships)

Description: In this domain, the right answer to a problem is easy to identify. Metaphor: Playing Checkers Example: Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) in an organization can solve simple problems.

Complicated (a domain of experts where we know the information we need, but we don’t have the answers)

Description: We have asked questions but have not received an answer. Metaphor: Playing Chess Example: The use of Lean Six Sigma (LSS) in solving problems.

Complex (the information we need is out there somewhere, but we don’t know what we’re looking for)

Description: The best way to determine if you have a Complex or Complicated system or problem is to figure out if you have an emergent complex adaptive system (CAS) – which will have a large number of agents interacting, learning, and adapting; thus, if you have a CAS, you are in the Complex domain. Metaphor: Playing Wei-chi (aka Go) Example: Using Systems Thinking v2.0 (DSRP) to solve complex (wicked) problems.

Chaotic (the realm of the unknown)

Description: Possessing an understanding of cause-and-effect is useless. Metaphor: Playing Twister Example: First responders and the military have to train for all possible scenarios. In this domain, it is very important to train yourself so you do not freeze during an unexpected situation (such as an active shooter).

Feeedback

7. Cue — Routine — Reward

Charles Duhigg writes about a powerful habit loop in The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. By understanding the habit loop, we can change bad habits by replacing them with healthy habits. The habit loop is a neurological loop consisting of the following:

Cue: The cue is anything that triggers the habit. Think of this as a tripwire. Routine: This is the routine you wish to change (i.e. smoking). Reward: The reward is the reason for change. It is the positive reinforcement for the new behavior.

Duhigg provides the following tips to short-circuit the habit loop. Let’s look at an example: Step 1: Identify the routine This is the behavior you wish to change. If you step on a scale and notice a large weight gain, then this will trigger the cue to lose weight. Step 2: Experiment with rewards Experiment with different rewards to see which one stick. If you write down every time you run — And you create a long chain of events — Then you will want to continue the chain (imagine a calendar with a string of check-marks illustrating how often you run). Step 3: Isolate the cue Duhigg says that we can ask ourselves (and record our answers) five things the moment an urge hits use in order to diagnose our habit:

- Where are you?

- What time is it?

- What’s your emotional state?

- Who else is around?

- What action preceded the urge? Step 4: Have a plan Duhigg found once we figure out our habit loop, we are then able to shift our behavior.

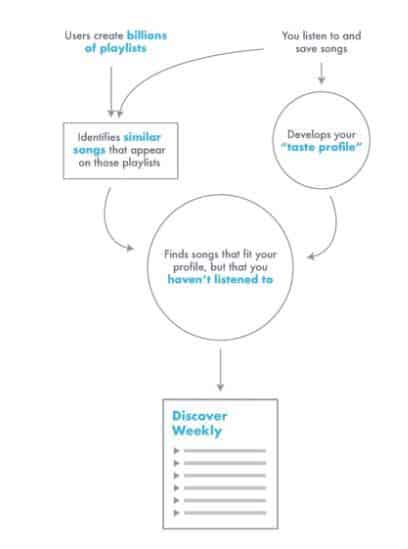

8. Algorithms (Killer tip!)

Algorithms are built off of and learn from feedback loops. This is why companies, such as Netflix and Spotify can successfuly recommend movies and music to you. In Swipe to Unlock: A Primer on Technology and Business Strategy, the authors illustrate the algorithm and feedback loop Spotify uses. It is a computer algorithm to find songs that fit your profile.

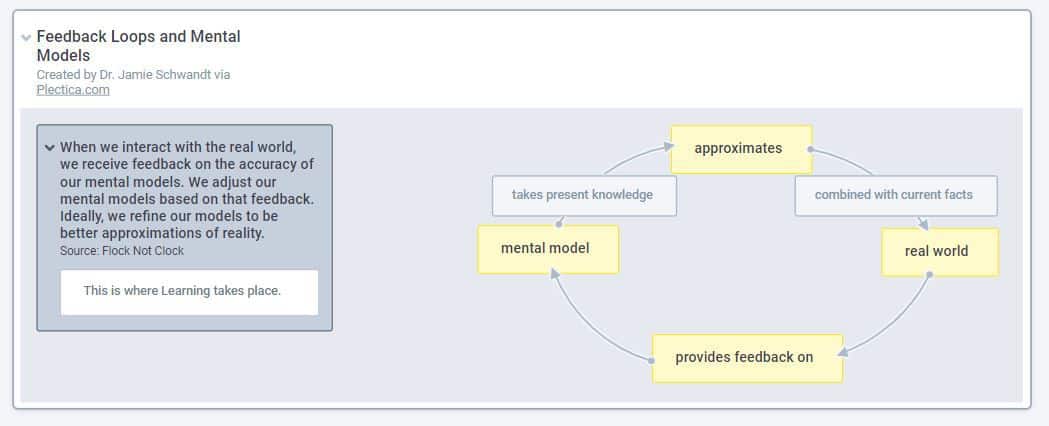

The authors discuss the Discover Weekly algorithm that starts by looking at two basic pieces of information. First, it looks at all songs you’ve listened to and liked enough to add to your library or playlists. They also mention that the algorithm is even smart enough to know if you skipped a song in the first 30 seconds. Second, it looks at all the playlists others have made, with the assumption that each playlist has a thematic connection. We can use computer algorithms, such as the Discover Weekly algorithm as an example of how to adapt and evolve our mental models. Our mental models are our own personal feedback loops and algorithms for how we live. In Flock Not Clock, Derek and Laura Cabrera write, Here is how this can work:

Our mental model (current knowledge) takes our present understanding of reality and approximates the real world (combined with current facts). This is the lens through which we view reality. Once we make the decision to act on our current knowledge, we then receive feedback from our environment. This feedback then changes our mental model — thus, this changes/revises our present knowledge. In essence, this is an algorithm for improvement.

9. OODA Loop

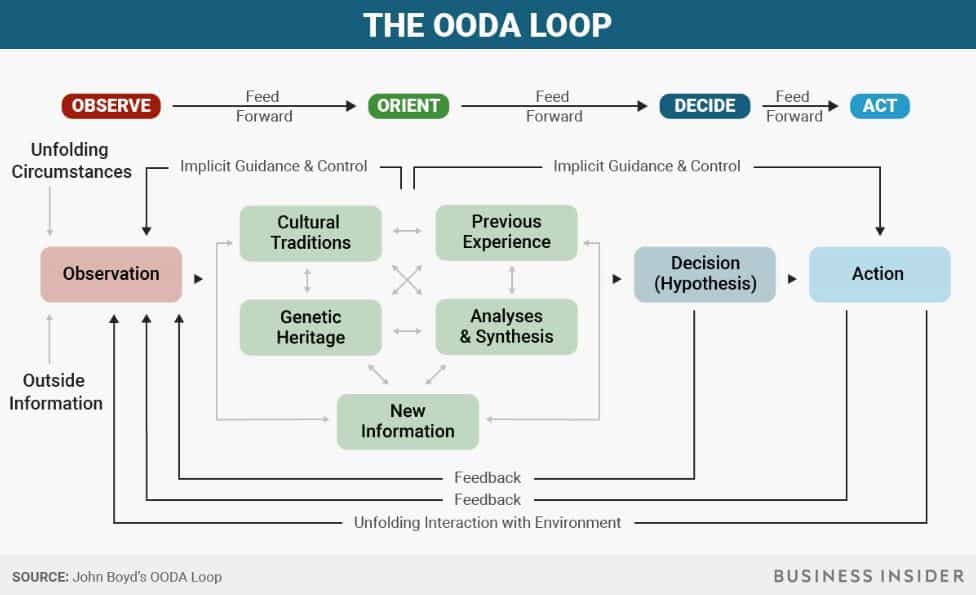

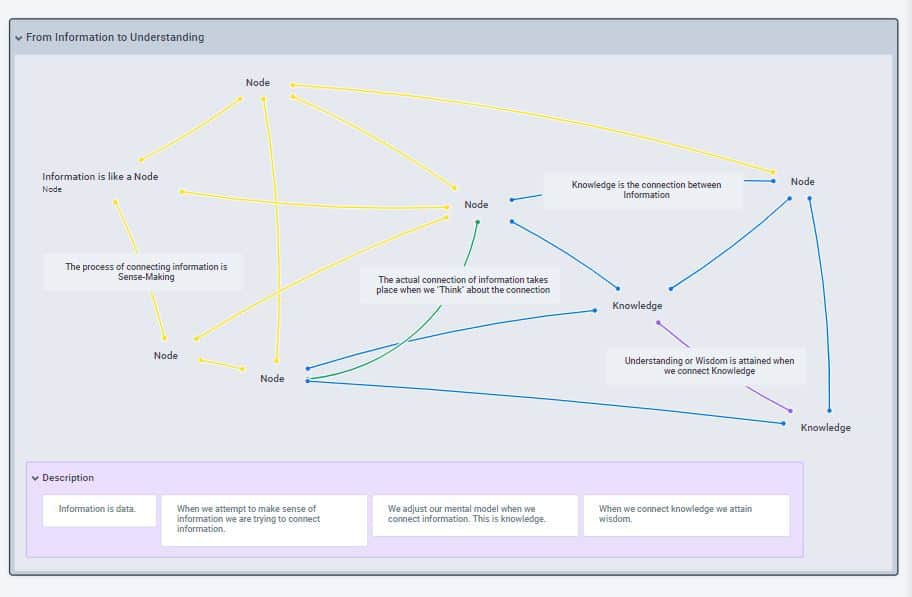

The OODA Loop was created by Colonel (Ret.) John Boyd. Without going into too much detail, I have adapted the OODA Loop as follows: It is a high-speed decision making and feedback process using simple rules to upgrade your critical thinking skills for a sharper mind. For a more detailed look at the OODA Loop, I recommend reading my article How to Upgrade Your Critical Thinking Skills for a Sharper Mind. In its simplest form, the OODA Loop is a high-speed decision making and feedback process in four stages: Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act. I am using the OODA Loop in my Emergent Learning concept as discussed in the VMCL portion of this article. I use it to move from information to understanding.

Observe In my course at FHSU, I have my students digest information to receive data. Essentially, information is data. Think of information as a node in a systems diagram. Orient I then help my students orient to the information in an attempt to make sense of the information. Sense-making is the process of connecting information. Decide When we connect information (connecting two nodes) we bring about knowledge. The Cabrera’s provide the perfect equation for knowledge: Knowledge = Information x Thinking Thus, we can only bring about Knowledge when we introduce students to “Thinking”. Act To truly understand a concept, we must act. When we connect knowledge we attain wisdom. This is done through practical application of concepts.

Final thoughts

Lastly, my hope is that these 9 game changing tips will provide you a clear picture of your future vision or goals. These missing puzzle pieces should assist you in filling in those gaps in your mind. Just remember, use questions to improve your vision, use simple rules to guide you to your vision, and always look for feedback for improvement. Featured photo credit: Unsplash via unsplash.com